When she was in her early twenties, my daughter asked me once how do you know whether to allow yourself to be vulnerable to another person. What hung in the air was a plea for protection from the risk of being hurt. It's the tipping point in a relationship. In order to love fully, you must cross that line and not look back. The risk of being hurt hangs at the precipice as we decide whether to step out into faith toward another or not. Some people never make it across.

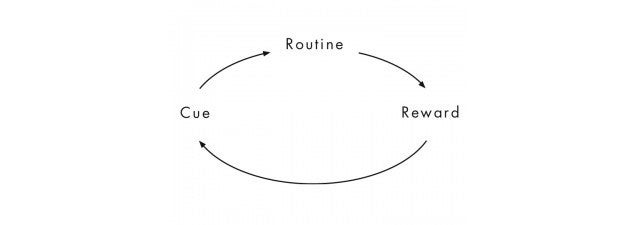

In the parable of the sower (Mathew 13: 18-23), Jesus instructs how the seed sown among thorns is the one who hears the word, but then worldly anxiety...chokes the word and it bears no fruit. For several decades, I encouraged beautiful women on my sales team to let go of anxiety about the outcome of their work, and simply apply themselves to the work, doing the best they could at serving others. Releasing concern about the outcome allowed a natural flow of their abilities to occur and positive results followed.

In my new writing career path, I am experiencing the same sort of anxiety about which I counseled many just a few years ago. It is an unfamiliar nervousness and hesitation. I'm accustomed to being assertive and bold in my pursuit of my goals. The core toggle point is the feeling of vulnerability about which my daughter queried me. A memoir by its very nature is deeply personal. As I get closer to releasing it, this very private side of my faith life is about to walk naked among my readers. I am self-conscious and doubtful of acceptance. Like the Emperor who had no clothes, an authentic memoirist has none either. The difference is he or she knows it.

If I take the same counsel I used to give, I will shake out my feelings of inadequacy like a sheet fresh from the wash and hang it in the wind to dry and billow freely. Without doing anything at all, a sheet hanging on a line in the wind restores peace to agitated souls, tired and weary, who gaze upon it. My goal of serving others by sharing what our Good Lord has done in, with and through me will be accomplished by simply hanging myself out to dry in Spirit wind, in my book's pages, after being washed in the blood of Christ, and rinsed in His Downey soft gift of peace.

I'm all wet, Lord. You have drenched me through the night. Hang me up. I'm ready for a new day of line drying, to smell fresh from the breeze of your Spirit, so that others may fall asleep on my sheets in your sweet, fragrant peace.

"Live in a manner worthy of the call you have received, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another through love..." St. Paul to the ephesians 4:1-2